Others like meditation on god's word Features >>

Meditations On Jesus

Soaking In God's Presence

The Pleasures Of God: Meditations On God’s Delight

God's Word For You "Fear Not"

The Passion Translation

Knowing God Intimately

Change Your Words And Choose Them To Heal

And The Angels Were Silent

40 Days To Discovering God's Big Idea For Your Life

To Be Like Jesus

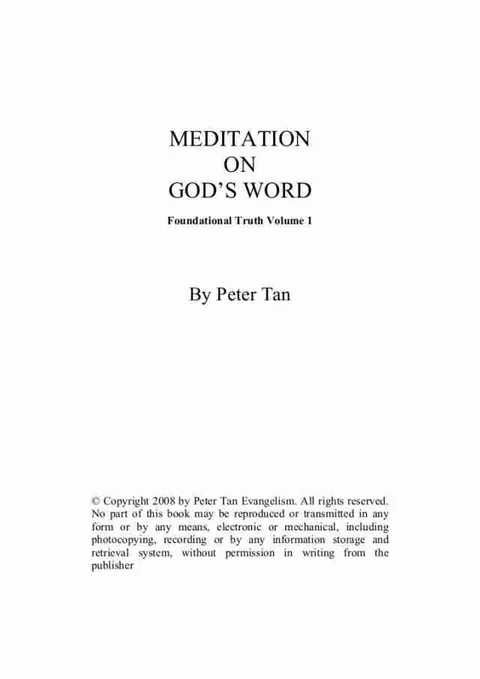

About the Book

"Peter Tan's book, 'Meditation on God's Word,' explores the power and significance of meditating on Scripture. The book delves into the benefits of regularly soaking in God's Word and offers practical guidance on how to effectively meditate on and apply the Bible to everyday life."

Carl F.H. Henry

Today Is Just in Time

His circumstances were a nightmare. Not only did he live in the land of whoredom, standing on the brink of national judgment, but his job seemed more like a sick joke than a divine commission. Go marry a prostitute and get her pregnant, God told Hosea, because I have a message to send my sinful people (Hosea 1:2). No prophet of Israel received convenient instructions, but this was about as rough as it ever got. Not to mention, all this drama — this real-life theater — was for a faithless people. Israel had it good from God, until they coopted his blessing to serve Baal, doubling down their opulence, partying hard, and forgetting all about the One who had called them out of slavery. The relationship between ancient Israel’s sin and their forgetfulness is not ironic. If sin makes people stupid (and it does), spiritual adultery makes us oblivious: She did not know that it was I who gave her the grain, the wine, and the oil, and who lavished on her silver and gold, which they used for Baal. . . . [Israel] went after her lovers and forget me, declares the Lord. (Hosea 2:8; 4:6, 10–12) They were filled, and their heart was lifted up; therefore they forgot me. (Hosea 13:6) I took them up by their arms, but they did not know that I healed them. (Hosea 11:3) Grace on the Edge Now the time had come to reap God’s wrath — hence the prophetic work of Hosea. “I will punish them for their ways and repay them for their deeds” (Hosea 4:9). The charges had piled up. Judgment was breathing down their necks. Any day now, we’d be saying if we were there, and things are about to blow. Wholesale captivity is right around the corner, and before that, an invading Assyrian army. But then there’s a call to repentance. The context is so pervasively negative, commentators have debated whether it’s serious or sarcasm. Come, let us return to the Lᴏʀᴅ; for he has torn us, that he may heal us; he has struck us down, and he will bind us up. After two days he will revive us; on the third day he will raise us up, that we may live before him. Let us know; let us press on to know the Lᴏʀᴅ; his going out is sure as the dawn; he will come to us as the showers, as the spring rains that water the earth. (Hosea 6:1–3) Hosea is for real. He means it. This book is laced with surprising words of grace; even in the midst of accusation, mercy is busting at the seams (Hosea 2:14–23; 3:1–5; 10:12; 11:1–12; 12:9; 14:1–9). In the rubble of Israel’s wickedness, in the aftermath of their apostasy, the plea still goes forth: Let us know him; Let us press on to know the Lord. Mighty in His Mercy It is a plea for us as much as for them. Know the Lord, Hosea says. Even in their mess, even in their shambled condition, when the icky-ness of their past sin is corroding the present, Hosea holds out the invitation: Today, would you turn? Will you press on to know him now? There is a theological fact to grasp here — or perhaps more, a divine emotion to feel. Just when all we can imagine is stern, hard, cold; there is warmth, eyes of hope, hands held forth. God is not like us, after all. Maybe one shot and we’re done. Maybe a few more here and there, depending on our mood, differing measures of grace, or various personalities. But not with God. How can I give you up, O Ephraim? How can I hand you over, O Israel? . . . My heart recoils within me; my compassion grows warm and tender. I will not execute my burning anger; I will not again destroy Ephraim; for I am God and not a man, the Holy One in your midst, and I will not come in wrath. (Hosea 11:8–9) As he told Moses so many years before, God tells us again: he is holy by his mercy — and it is always available to his people if they would but turn and trust him. Turning Today Which means, no matter what your yesterday looked like, the invitation is open still. Today is just in time. Like Puddleglum told Eustace and Jill, after they had muffled their obedience, while they were clearly frustrated, feeling like idiots, assuming they’d ruined everything, “Aslan’s instructions always work: there are no exceptions. But how to do it now — that’s another matter” (Silver Chair, 121). Stop for a moment, and think. It does not matter what happened yesterday, or last year, or that one time back then. What matters is this moment, now, when the mercy of God in Jesus is extended to you. All is not calloused. Remember, Jesus died in your place and took the wrath that belongs to you, if you would but trust him. As sure as the sun comes up, as sure as it rains, God has promised mercy to his people when they repent (1 John 1:9; 2 Chronicles 7:14). God’s mercy is always available to his people if they would but turn and trust him. Whatever wreck your life might be, however nightmarish your circumstances seem, Jesus is ready to embrace you. His righteousness is ready to clothe you. The mighty wave of his mercy is growing higher and higher, soon to crash over your soul, if you would just turn, if you would but seek him. Would you? Even in the midst of your mess, would you turn to him? Let us know; let us press on to know the Lord. Article by Jonathan Parnell Pastor, Minneapolis, Minnesota

-480.webp)