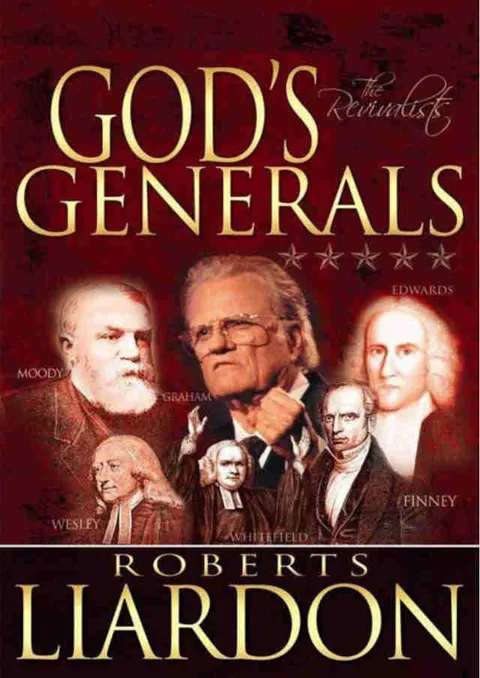

God's Generals - The Revivalists Order Printed Copy

- Author: Roberts Liardon

- Size: 1.59MB | 427 pages

- |

Others like god's generals - the revivalists Features >>

-160.webp)

God's Generals (A. A. Allen)

God's Generals: The Revivalists

Fire On The Earth - Eyewitness Reports From The Azusa Street Revival

God's Generals: The Roaring Reformers

God’s Generals: John Alexander Dowie

God's Generals - The Martyrs

God's Generals: Jack Coe

-160.webp)

God's Generals (William Branham)

God's Generals: The Martyrs

-160.webp)

God's Generals (Maria Woodworth)

About the Book

"God's Generals: The Revivalists" by Roberts Liardon is a comprehensive look at the lives and ministries of some of the most influential revivalists in Christian history. The book explores the lives of figures such as John Wesley, Charles Finney, and Smith Wigglesworth, detailing their struggles, triumphs, and the impact they had on the Christian faith. Liardon delves into their unique gifts, spiritual encounters, and the powerful revivals they led, inspiring readers to pursue a deeper relationship with God and a passion for spreading the Gospel.

Rosaria Butterfield

4 Simple Steps to a New Financial Beginning

The start of a new year is a terrific time to begin your journey toward financial security and investing success by making it a priority to pay off credit cards, car loans, and other short-term debts. That’s right, the first financial fitness test you need to pass is the "debt" test. Webster’s says that debt is anything you’re "bound to pay or perform; the state of owing something." Using that definition, very few Americans are free of debt. Why is getting debt-free the first step toward a sound investing strategy? Because it’s unwise to take on the risks that come with investing unless you have staying power. That means you don’t want to be in a position where circumstances unrelated to your investment strategy force you to sell your holdings and use the money elsewhere, such as for interest and debt payments. Also, for Christians, debts are moral as well as legal obligations and they must be honorably met no matter the circumstances. The late Dr. D. James Kennedy once gave a sermon in which he read a poem called "The Land of Beginning Again." He then presented Christ as the King of the Land of Beginning Again. All of us have experienced our share of errors, failures, and missed opportunities. We all have things that we would do differently if given a second chance. What wonderful news that, in Christ, the slate is wiped clean and we do have the opportunity of beginning again. In a similar fashion, many who have become weighed down by debt wish they could get free. They have learned that the satisfaction that comes with spending is brief indeed compared to the pressure of making monthly payments which often go on for years. For some, it seems hopeless. You may sometimes feel this way yourself. If so, take heart! You can make significant strides this year. It will require planning, discipline, sacrifice, and singleness of purpose, and there are some excellent books that can help: • Check out Mary Hunt's website DebtProofLiving.com, which also links to her very helpful blog, "Money Rules, Debt Stinks." Through her website and books, Mary has become the queen of frugal living. Her advice is practical and witty. That’s why we use her articles regularly in SMI. • Free and Clear: God’s Road Map to Debt-Free Living by Howard Dayton is a compassionate guide for those struggling with debt. Dayton’s Compass1.org website offers this and many other helpful resources. • Dave Ramsey has made a big splash helping listeners to his radio program get debt-free. His Financial Peace Revisited is worth a look. A friend of mine likes to say that the most powerful force in the universe (humanly speaking, of course) is singleness of purpose. Individuals or groups, no matter how determined, disciplined, or talented, will never realize their potential for growth and accomplishment without singleness of purpose. Their time, money, and energies must be focused on common goals. One thing that successful people seem to have in common is an emphasis on — perhaps that’s putting it too lightly, make that an obsession about — setting goals. Without singleness of purpose and specific goals, we can become like the person Scripture describes as double-minded. "That man should not think he will receive anything from the Lord; he is a double-minded man, unstable in all he does" (James 1:7-8). So let me encourage you to engage in a meaningful goal-setting exercise as you work to get debt-free. Here are some suggestions for effective goal-setting in any area of life; adapt them to your financial situation. Set goals that are consistent with God’s Word. Many successful people have accomplished much, yet remain unhappy. Having singleness of purpose toward the wrong goals only leads to wrong results. Examine your motivations, as well as your actions, in the light of God’s wisdom. Ask God for His guidance. This is not the same as having scripturally sound goals. This has more to do with having the wisdom needed to set the right personal priorities. God promises to guide us if we’re willing to submit to Him (Prov. 3:5-6). It’s not: "Show me Your will, Lord, so I can decide if I’m willing." Rather, it’s: "Before You even reveal Your will to me, Lord, the answer is yes." If married, set your goals together. If two people have become "one flesh," it’s critical that they have a singleness of purpose in their commitment toward common goals. Few areas will so quickly affect a couple’s relationship as a financial plan that limits their spending freedom because it brings mutually conflicting goals into the open. If you can’t reach a meeting of the minds on what your priorities should be, perhaps the marriage relationship itself needs some work. Put your goals in writing, signing your name and date. This helps cement in your thinking that you really have made a firm commitment of your will to achieving your goals. It is also helpful to have your goals posted where you will see them daily as additional motivation to stay the course when the inevitable temptations to compromise arise. Austin Pryor