Others like god's generals - the martyrs Features >>

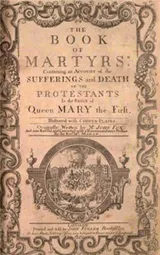

Foxes Books Of Martyrs

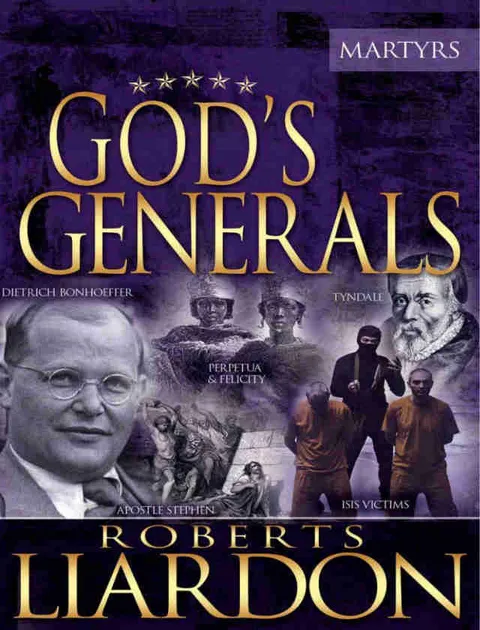

God's Generals: The Martyrs

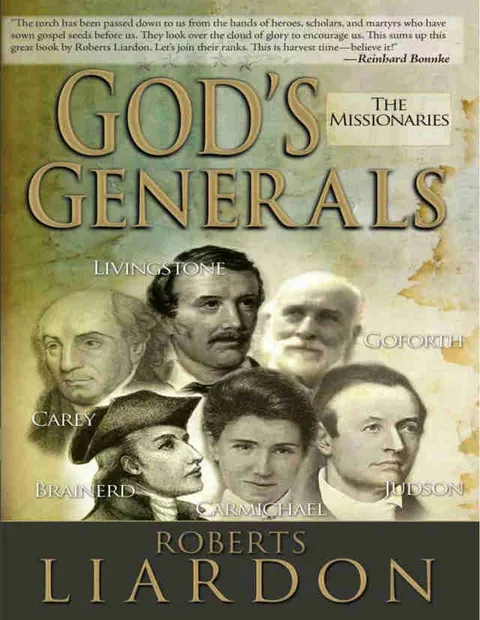

God's Generals - The Missionaries

God's Generals: Jack Coe

Hearts Of Fire - Eight Women In The Underground Church And Their Stories Of Costly Faith

-160.webp)

God's Generals (A. A. Allen)

God's Generals: The Missionaries

-160.webp)

God's Generals (Charles F. Parham)

God's Generals: William Branham

-160.webp)

Foxes Book Of Martyrs (History Of The Lives, Sufferings, And Triumphant Deaths Of The Primitive Protestant Martyrs)

About the Book

"God's Generals - The Martyrs" by Roberts Liardon is a compilation of biographies of Christian martyrs who gave their lives for their faith throughout history. The book highlights their courage, faith, and devotion to God, serving as a tribute to their sacrifice and a source of inspiration for readers to stand firm in their own faith.

Nabeel Qureshi

I Have Found the Real God

I praise and thank God because since coming to here to Saudi Arabia I have found the real God. I accepted Jesus as my personal Lord and Savior and was baptized. After I explained the plan of salvation to my wife, she could understand why I wanted to be born again, and in 2013 she accepted Jesus as her Lord and Savior. (Now, I am not afraid for my wife to know that I am a Christian…) I had once bought a house for my mom, but sadly, and without informing me, she had left the house after only three months and gone back to our old house. About that time, a woman we knew had a friend who was expecting a baby but was planning to give it away as soon as it was born, and I asked to talk to her. I asked her, what has happened that you would give your baby away? She answered that she could not provide for the needs of the baby; then she said, I will give this Baby to you. I said I must first talk to my wife, and then I will come back. I stopped on the way home to visit my uncle. When he learned that I wanted to adopt the baby, he did not approve. I said, “Uncle I will accept what God has given to me. I didn't plan to find a baby, but for almost ten years my wife and I have waited, and my wife is so tired, and now we have this offer, so maybe this is the answer from God.” My Uncle replied, but you know that girl is a prostitute. I said, “Yes, but the mistake of the mother is not the mistake of the baby. If the baby died because she couldn’t provide it would be on my conscience; besides, if God has answered my prayer, I promise to God that I will teach her how to follow Jesus…” When I arrived home, my wife was at work at the office, so I paid her a surprise visit, and she was very happy. After a while, I told her that I would come back after her workday was finished. When I went back to my wife’s office, I talked to her about the baby. My wife said, “She has two more months before she delivers the baby; we must first talk to her.” That night my wife and I went to the woman’s little house. My wife told her that if she had anyone else who wanted to adopt the baby, to give it to them, but if she could not find anyone it would mean that God had planned it for us, and we would accept. After a month had gone by I visited the woman again, and she said that she had not given the baby to anyone. When she said that, I closed my eyes and said to God, “Thank you Lord for this opportunity you have given to my wife and me.” Even though I did not yet know if it was a boy or a girl, I was happy. I arranged for all the food and everything she might need and then left for Saudi Arabia. I returned a month later just in time for a precious baby girl to be delivered. The baby was born in the house I had bought for my parents, so I said to the birth mother, “I want you to stay in this house.” My daughter is growing and will be two years old on November 16, 2015. She is beautiful and very loveable, and we are so blessed. As soon as my daughter is a little older, my wife and I will teach her how important God is in our lives. We know that our precious daughter is from God, because ever since we had been married, almost ten years, I would often lose hope in having a baby because my wife has some problems with her ovaries. She does not yet know how to talk, but already knows to pray before meals. I am making plans for my vacation this coming November 02, 2015 in the Philippines, to prepare a party for my beautiful two-year-old daughter... Thanks be to God, all my prayers have been answered in His perfect time. I thank Him every day and will never forget this wonderful gift. Please help me pray that I can also share the Gospel with my relatives, friends, and visitors, and tell them about accepting Jesus Christ as their personal Lord and Savior. It is my desire for them to hear about God, even if it is only a short message. I know God loves me, and my family. Though I have encountered many trials, with the help of God, I have overcome them all. Thank you, and God bless