God's Generals: The Missionaries Order Printed Copy

- Author: Roberts Liardon

- Size: 3.23MB | 358 pages

- |

Others like god's generals: the missionaries Features >>

-160.webp)

God's Generals (Charles F. Parham)

God’s Generals: John Alexander Dowie

A God Entranced Vision Of All Things: The Legacy Of Jonathan Edwards

God's Generals: The Revivalists

-160.webp)

God's Generals (Jack Coe)

God's Generals: The Martyrs

God's Generals: Why They Succeeded And Why Some Failed

-160.webp)

God's Generals (William J. Seymour)

God's Generals: Evan Roberts

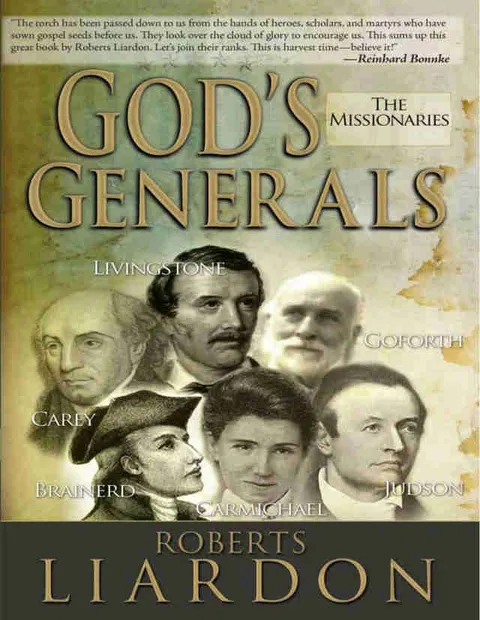

God's Generals - The Missionaries

About the Book

"God's Generals: The Missionaries" by Roberts Liardon provides a detailed account of some of the most influential missionaries in Christian history, highlighting their extraordinary faith, courage, and dedication to spreading the Gospel around the world. Liardon's book offers inspiring stories of missionaries like David Livingstone, Amy Carmichael, and Hudson Taylor, showing how their passion for God's work impacted countless lives and shaped the course of history.

Andrew Fuller

Fuller was born in Soham, Cambridgeshire, England, where in 1775 he was ordained pastor of the Baptist church. Originally schooled in the hyper-Calvinist theology then prevalent in parts of the Particular Baptist denomination, he became convinced in 1775 that the hyper-Calvinist position was not scriptural. In 1785 he published The Gospel Worthy of All Acceptation, which did much to prepare his denomination for accepting this missionary obligation. As pastor in Kettering, Northamptonshire, from 1783, Fuller became firm friends with John Sutcliff of Olney, John Ryland of Northampton, and later the young William Carey. The strengthening missionary vision of this group bore fruit on October 2, 1792, when the Particular Baptist Society for Propagating the Gospel among the Heathen (later known as the Baptist Missionary Society) was formed in the home of one of Fuller’s deacons in Kettering. Fuller was appointed secretary. Until his death he combined the demands of a busy pastorate with managing the affairs of the BMS. He traveled extensively to raise funds for the society, especially in Scotland, which he visited five times.

Brian Stanley, “Fuller, Andrew,” in Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions, ed. Gerald H. Anderson (New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 1998), 230-231.

This article is reprinted from Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions, Macmillan Reference USA, copyright © 1998 Gerald H. Anderson, by permission of Macmillan Reference USA, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

Pastor, apologist, and promoter of missions

Though not university trained, Andrew Fuller was recognized by his contemporaries as the preeminent Baptist theologian of their day and was awarded honorary doctor of divinity degrees by both Princeton (1798) and Yale (1805). Fuller’s published works, preaching ministry and churchmanship was, perhaps, the primary mediating agency between the transatlantic evangelical revival and the English Particular (or “Calvinist”) Baptists who had distanced themselves from what was largely at the start an Anglican renewal movement. Fuller was also well known as a co-founder of the Baptist Missionary Society (or, the Particular Baptist Society for the Propagation of the Gospel Amongst the Heathen [est. 1792]), on whose behalf he itinerated regularly in the British Isles, lobbied the East India Company, and wrote numerous letters and magazine articles during his twenty-two year tenure as its first general secretary. He was an opponent of the British slave trade and, though a dissenting non-Anglican, an acquaintance of William Wilberforce and other members of the Clapham sect, who were key allies in Parliament. He was a pastors’ pastor who exerted no small influence for evangelical doctrine and a missionary vision through the many ordination sermons he preached. From 1782 until his death in 1815 he served as pastor of the Kettering Baptist Church and was frequent chairman of the Northamptonshire Association, a consortium which included the likes of William Carey, Samuel Pearce, John Sutcliffe, and John Ryland, Jr.

Fuller was born in 1754 at Wicken, Cambridgeshire, to non-conformist parents who worked a dairy farm. In 1775, six years after his own conversion experience, he was inducted as pastor of the forty-seven member church in Soham, where he had received his baptism and was a member. In 1776 he married his first wife, Sarah Gardiner, with whom he had eleven children, only three surviving beyond early childhood. Sarah would die in 1792, less than two months before the founding of the British Missionary Society (BMS). During this seven year pastorate, Fuller immersed himself in the literary culture of Anglo-American evangelical Calvinism. He cultivated his theological perspective and ministry philosophy by ardently studying the Scriptures alongside the works of the Reformers, seventeenth-century Puritans (especially John Owen), early English Baptists like John Bunyan and John Gill, as well as the writings of American Congregationalist philosopher-theologian and pastor, Jonathan Edwards. Fuller also acknowledged in his most popular book, The Gospel Worthy of All Acceptation (1781), the influence of the lives of John Eliot and David Brainerd, both late missionaries to the native Americans. The Gospel Worthy was Fuller’s remonstration against the hyper-Calvinism that negated the propriety of evangelistic appeals. By the 1790s, evangelical (or “strict”) Calvinism was known in England as “Fullerism” (vs. “High” or hyper-Calvinism). The Gospel its Own Witness (1800) was Fuller’s refutation of Deism. Fuller gained a reputation by these two books, especially, for publically, clearly and systematically opposing in print whatever widely held doctrines he believed were undermining the church and its mission.

In the Northamptonshire Assocation Fuller was a member of a thriving intellectual community most influenced by Edwards. In 1784 John Sutcliff initiated a “concerts of prayer” movement similar to the program suggested by Edwards in An Humble Attempt to Promote Explicit Agreement and Visible Union of God’s People in Extraordinary Prayer (1748). Baptist congregations prayed monthly for the spread of the gospel and the kingdom of Christ to the ends of the earth through all denominations. In 1791, Sutcliff, Fuller and Samuel Pearce each preached at significant events (Sutcliff and Fuller at the association meeting of pastors, Pearce at William Carey’s ordination) on the duty of the church to evangelize the whole inhabitable globe. Fuller based his appeal on the eternal truth of the gospel, the eternal relevance of the gospel, the eternal power of the gospel, and the circumstances of the age that made missionary endeavors possible and obligatory.(1) Carey’s much touted association sermon from Isaiah 54:2-3 in May of 1792 did not arise in a vacuum. The influence was mutual between Carey and Fuller, both being influenced by Robert Hall, Sr. and Samuel Pearce (who had been inspired by the Methodist Thomas Coke in Birmingham).

On October 2, 1792, the BMS was formed with Fuller its first secretary and the assumption that its support would come largely from the churches of the Northamptonshire Association. When the society sent Carey and John Thomas to India the following year, Fuller preached their commissioning service from John 20:21 (“As the Father has sent me, even so I [Christ] am sending you.”). Fuller believed the mission’s raison d’être was the uniqueness of Christ and Christian responsibility to proclaim him. Bible translation and evangelism should take priority. Hindus were not desiring or seeking the Christian Scriptures. But to ignore and neglect anyone in an unconverted state is inconsistent with the love of God and man. In addition, God had promised the messiah the inheritance of the nations (An Apology for the Late Christian Missions to India, 1808). The church is obligated to employ means and make an effort as the means God uses to fulfill that promise to Christ. Obstacles are merely a test to sincerity of faith.

Fuller spent up to ten hours per day in correspondence and reporting for the BMS. He contributed articles to Evangelical Magazine, Missionary Magazine, Quarterly Magazine, Protestant Dissenters’ Magazine, Biblical Magazine, and Theological Miscellany. He sought financial support via letters and by an average of three months of vigorous itineration each year among various evangelical churches in Scotland, Ireland, Wales and England. John Ryland, Jr. wrote of Fuller’s style, that he, “…always disliked violent pressing for contributions, and attempting to outvie other societies: he chose rather to tell a plain, unvarnished tale; and he generally told it with good effect.”(2) Through written correspondence he “pastored” the missionaries in the field while maintaining a decentralized approach to mission administration. He believed the missionaries were more capable of governing themselves and that the time required for correspondence made central control impractical anyway.

The security of the unlicensed Baptist missionary society’s place in the British Empire was frequently tenuous up to 1813. Fuller occasionally had to petition Parliament or the Board of Control for continued tolerance of the BMS. Muslim irritation at the Christian missionary presence and the conversion of some Indians from Islam had been blamed for the Vellore Mutiny of 1806. Thomas Twining had openly claimed efforts at conversion were contradictory to “the mild and tolerant spirit of Christianity.” Fuller responded to Twining and other English defenders of Hinduism with his three-part Apology for the Late Christian Missions to India (1808) in which he argued for a toleration of religion that allows all religious views as well as efforts to persuade through reasonable means. He attributed several social ills, like ritual infanticide and sati, to Hinduism, and commended the missionaries for trying to put an end to such practices. Fuller was also a critic of the “detestable traffic” of the African slave trade, asserting it made England deserving of ruin at the hands of the French (from whose invasion he urged prayer that God would mercifully protect England). The prosperity of the empire should not come at the expense of other human beings. Patriotism must “harmonize” with “good will toward [other] men.”(3) On the other hand, Fuller often counseled BMS missionaries not to become “entangled” in political concerns which were “only affairs of this life” and endangered colonial toleration of the mission.(4) Because Jesus accomplished “moral revolution” in the heart, loyalty to the British government, rather than republicanism, should be encouraged as far as it is compatible with Christian commitments.(5)

Fuller, the pastor of families in England and abroad, counseled missionary families to nurture a deep spirituality for the sake of attaining the character commensurate with the nature of the gospel and their mission. Fuller knew the vicissitudes of even the Christian heart, and the “spiritual advantage” of engaging in mission. Reflecting in his diary on July 18, 1794, he wrote:

Within the last year or two, we have formed a missionary society; and have been enabled to send out two of our brethren to the East Indies. My heart has been greatly interested in this work. Surely I never felt more genuine love to God and to his cause in my life. I bless God that his work has been a means of reviving my soul. If nothing comes of it, I and many others have obtained a spiritual advantage.(6)

Fuller died in 1815. The epitaph stone for Fuller in the Kettering meeting house says he devoted his life for the prosperity of the BMS.(7) One biographer has said Fuller “lived and died a martyr to the mission.”(8) After December, 1794, he was assisted in life by his second wife, Ann Coles. Fuller also spent himself itinerating for the British and Foreign Bible Society after it was founded in 1804. His many occasional writings and sermon manuscripts reveal a love for the gospel message itself and the life-orienting impact of Bible texts such as Matthew 28:16-20 and Mark 16:15-16; John 12:36 and 20:21; and Romans 10:9, 14-17. Fuller is noted today for making a significant contribution to the revitalization of Particular (Calvinist) Baptist life in late eighteenth century England as well as for being a key figure in the historic turn toward a proliferation of free Protestant missionary societies at the beginning of the Great Century.

Fuller was born in Soham, Cambridgeshire, England, where in 1775 he was ordained pastor of the Baptist church. Originally schooled in the hyper-Calvinist theology then prevalent in parts of the Particular Baptist denomination, he became convinced in 1775 that the hyper-Calvinist position was not scriptural. In 1785 he published The Gospel Worthy of All Acceptation, which did much to prepare his denomination for accepting this missionary obligation. As pastor in Kettering, Northamptonshire, from 1783, Fuller became firm friends with John Sutcliff of Olney, John Ryland of Northampton, and later the young William Carey. The strengthening missionary vision of this group bore fruit on October 2, 1792, when the Particular Baptist Society for Propagating the Gospel among the Heathen (later known as the Baptist Missionary Society) was formed in the home of one of Fuller’s deacons in Kettering. Fuller was appointed secretary. Until his death he combined the demands of a busy pastorate with managing the affairs of the BMS. He traveled extensively to raise funds for the society, especially in Scotland, which he visited five times.

Brian Stanley, “Fuller, Andrew,” in Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions, ed. Gerald H. Anderson (New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 1998), 230-231.

This article is reprinted from Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions, Macmillan Reference USA, copyright © 1998 Gerald H. Anderson, by permission of Macmillan Reference USA, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

Pastor, apologist, and promoter of missions

Though not university trained, Andrew Fuller was recognized by his contemporaries as the preeminent Baptist theologian of their day and was awarded honorary doctor of divinity degrees by both Princeton (1798) and Yale (1805). Fuller’s published works, preaching ministry and churchmanship was, perhaps, the primary mediating agency between the transatlantic evangelical revival and the English Particular (or “Calvinist”) Baptists who had distanced themselves from what was largely at the start an Anglican renewal movement. Fuller was also well known as a co-founder of the Baptist Missionary Society (or, the Particular Baptist Society for the Propagation of the Gospel Amongst the Heathen [est. 1792]), on whose behalf he itinerated regularly in the British Isles, lobbied the East India Company, and wrote numerous letters and magazine articles during his twenty-two year tenure as its first general secretary. He was an opponent of the British slave trade and, though a dissenting non-Anglican, an acquaintance of William Wilberforce and other members of the Clapham sect, who were key allies in Parliament. He was a pastors’ pastor who exerted no small influence for evangelical doctrine and a missionary vision through the many ordination sermons he preached. From 1782 until his death in 1815 he served as pastor of the Kettering Baptist Church and was frequent chairman of the Northamptonshire Association, a consortium which included the likes of William Carey, Samuel Pearce, John Sutcliffe, and John Ryland, Jr.

Fuller was born in 1754 at Wicken, Cambridgeshire, to non-conformist parents who worked a dairy farm. In 1775, six years after his own conversion experience, he was inducted as pastor of the forty-seven member church in Soham, where he had received his baptism and was a member. In 1776 he married his first wife, Sarah Gardiner, with whom he had eleven children, only three surviving beyond early childhood. Sarah would die in 1792, less than two months before the founding of the British Missionary Society (BMS). During this seven year pastorate, Fuller immersed himself in the literary culture of Anglo-American evangelical Calvinism. He cultivated his theological perspective and ministry philosophy by ardently studying the Scriptures alongside the works of the Reformers, seventeenth-century Puritans (especially John Owen), early English Baptists like John Bunyan and John Gill, as well as the writings of American Congregationalist philosopher-theologian and pastor, Jonathan Edwards. Fuller also acknowledged in his most popular book, The Gospel Worthy of All Acceptation (1781), the influence of the lives of John Eliot and David Brainerd, both late missionaries to the native Americans. The Gospel Worthy was Fuller’s remonstration against the hyper-Calvinism that negated the propriety of evangelistic appeals. By the 1790s, evangelical (or “strict”) Calvinism was known in England as “Fullerism” (vs. “High” or hyper-Calvinism). The Gospel its Own Witness (1800) was Fuller’s refutation of Deism. Fuller gained a reputation by these two books, especially, for publically, clearly and systematically opposing in print whatever widely held doctrines he believed were undermining the church and its mission.

In the Northamptonshire Assocation Fuller was a member of a thriving intellectual community most influenced by Edwards. In 1784 John Sutcliff initiated a “concerts of prayer” movement similar to the program suggested by Edwards in An Humble Attempt to Promote Explicit Agreement and Visible Union of God’s People in Extraordinary Prayer (1748). Baptist congregations prayed monthly for the spread of the gospel and the kingdom of Christ to the ends of the earth through all denominations. In 1791, Sutcliff, Fuller and Samuel Pearce each preached at significant events (Sutcliff and Fuller at the association meeting of pastors, Pearce at William Carey’s ordination) on the duty of the church to evangelize the whole inhabitable globe. Fuller based his appeal on the eternal truth of the gospel, the eternal relevance of the gospel, the eternal power of the gospel, and the circumstances of the age that made missionary endeavors possible and obligatory.(1) Carey’s much touted association sermon from Isaiah 54:2-3 in May of 1792 did not arise in a vacuum. The influence was mutual between Carey and Fuller, both being influenced by Robert Hall, Sr. and Samuel Pearce (who had been inspired by the Methodist Thomas Coke in Birmingham).

On October 2, 1792, the BMS was formed with Fuller its first secretary and the assumption that its support would come largely from the churches of the Northamptonshire Association. When the society sent Carey and John Thomas to India the following year, Fuller preached their commissioning service from John 20:21 (“As the Father has sent me, even so I [Christ] am sending you.”). Fuller believed the mission’s raison d’être was the uniqueness of Christ and Christian responsibility to proclaim him. Bible translation and evangelism should take priority. Hindus were not desiring or seeking the Christian Scriptures. But to ignore and neglect anyone in an unconverted state is inconsistent with the love of God and man. In addition, God had promised the messiah the inheritance of the nations (An Apology for the Late Christian Missions to India, 1808). The church is obligated to employ means and make an effort as the means God uses to fulfill that promise to Christ. Obstacles are merely a test to sincerity of faith.

Fuller spent up to ten hours per day in correspondence and reporting for the BMS. He contributed articles to Evangelical Magazine, Missionary Magazine, Quarterly Magazine, Protestant Dissenters’ Magazine, Biblical Magazine, and Theological Miscellany. He sought financial support via letters and by an average of three months of vigorous itineration each year among various evangelical churches in Scotland, Ireland, Wales and England. John Ryland, Jr. wrote of Fuller’s style, that he, “…always disliked violent pressing for contributions, and attempting to outvie other societies: he chose rather to tell a plain, unvarnished tale; and he generally told it with good effect.”(2) Through written correspondence he “pastored” the missionaries in the field while maintaining a decentralized approach to mission administration. He believed the missionaries were more capable of governing themselves and that the time required for correspondence made central control impractical anyway.

The security of the unlicensed Baptist missionary society’s place in the British Empire was frequently tenuous up to 1813. Fuller occasionally had to petition Parliament or the Board of Control for continued tolerance of the BMS. Muslim irritation at the Christian missionary presence and the conversion of some Indians from Islam had been blamed for the Vellore Mutiny of 1806. Thomas Twining had openly claimed efforts at conversion were contradictory to “the mild and tolerant spirit of Christianity.” Fuller responded to Twining and other English defenders of Hinduism with his three-part Apology for the Late Christian Missions to India (1808) in which he argued for a toleration of religion that allows all religious views as well as efforts to persuade through reasonable means. He attributed several social ills, like ritual infanticide and sati, to Hinduism, and commended the missionaries for trying to put an end to such practices. Fuller was also a critic of the “detestable traffic” of the African slave trade, asserting it made England deserving of ruin at the hands of the French (from whose invasion he urged prayer that God would mercifully protect England). The prosperity of the empire should not come at the expense of other human beings. Patriotism must “harmonize” with “good will toward [other] men.”(3) On the other hand, Fuller often counseled BMS missionaries not to become “entangled” in political concerns which were “only affairs of this life” and endangered colonial toleration of the mission.(4) Because Jesus accomplished “moral revolution” in the heart, loyalty to the British government, rather than republicanism, should be encouraged as far as it is compatible with Christian commitments.(5)

Fuller, the pastor of families in England and abroad, counseled missionary families to nurture a deep spirituality for the sake of attaining the character commensurate with the nature of the gospel and their mission. Fuller knew the vicissitudes of even the Christian heart, and the “spiritual advantage” of engaging in mission. Reflecting in his diary on July 18, 1794, he wrote:

Within the last year or two, we have formed a missionary society; and have been enabled to send out two of our brethren to the East Indies. My heart has been greatly interested in this work. Surely I never felt more genuine love to God and to his cause in my life. I bless God that his work has been a means of reviving my soul. If nothing comes of it, I and many others have obtained a spiritual advantage.(6)

Fuller died in 1815. The epitaph stone for Fuller in the Kettering meeting house says he devoted his life for the prosperity of the BMS.(7) One biographer has said Fuller “lived and died a martyr to the mission.”(8) After December, 1794, he was assisted in life by his second wife, Ann Coles. Fuller also spent himself itinerating for the British and Foreign Bible Society after it was founded in 1804. His many occasional writings and sermon manuscripts reveal a love for the gospel message itself and the life-orienting impact of Bible texts such as Matthew 28:16-20 and Mark 16:15-16; John 12:36 and 20:21; and Romans 10:9, 14-17. Fuller is noted today for making a significant contribution to the revitalization of Particular (Calvinist) Baptist life in late eighteenth century England as well as for being a key figure in the historic turn toward a proliferation of free Protestant missionary societies at the beginning of the Great Century.

The Difficult Habit of Quiet

The habit of quiet may be harder today than ever before. Don’t get me wrong: it’s always been hard. The rise and spread of technology, however, tends to crowd out quiet even more. Now that we can carry the whole wide and wild world in our pockets, it’s that much harder to keep the world at bay. Our phones always promise another update to see, image to like, website to visit, game to play, text to read, stream to watch, forecast to monitor, podcast to download, headline to scan, article to skim, score to check, price to compare. That kind of access, and semblance of control, can begin to make quiet moments feel like wasted ones. Who could sit and be still while so much life rushes by? Even if we don’t immediately pick up our phones, we’re often still held captive by them, wondering what new they might hold — what we might be missing. As hard as quiet might be to come by, however, it’s still a life-saving, soul-strengthening habit for any human soul. The God who made this wide and wild world, and who molded our finite and fragile frames, says of us, “In quietness and in trust shall be your strength” (Isaiah 30:15). In days filled with noise, do you still find time to be this kind of strong? Or has stress and distraction slowly eroded your spiritual health? How often do you stop to be quiet? What God Does with Quiet What kind of quietness produces strength? Not all quietness does. We could sell our televisions, give away our phones, move to the countryside, and still be as weak as ever. No, “in quietness and in trust shall be your strength.” The quiet we need is a quiet filled with God. Quietness becomes strength only when our stillness says that we need him. Be still, and know that I am God. I will be exalted among the nations, I will be exalted in the earth! (Psalm 46:10) This still, trusting quietness defies self-reliance. Quietness can preach reality to our souls like few habits can. It says that he is God, and we are not; he knows all, and we know little; he is strong, and we are weak. Quietness widens our eyes to the bigness of God and the smallness of us. It brings us low enough to see how high and wise and worthy he is. You can begin to see why quietness can be so hard. It’s deeply (sometimes ruthlessly) humbling. For it to say something true and beautiful about God, it first says something true and devastating about us. Our quietness says, “Without him, you can do nothing.” Our refusal to be quiet, on the other hand, says, “I can do a whole lot on my own” — and that feels good to hear. It just robs us of the real strength and help we might have found. God strengthens the quiet with his strength, because quietness turns weakness and neediness into worship (2 Corinthians 12:9–10). We get the strength and help and joy; he gets the glory. But You Were Unwilling The context of Isaiah’s words, however, is not inspiring, but sobering. God says to his people, “In returning and rest you shall be saved; in quietness and in trust shall be your strength.” But you were unwilling . . . (Isaiah 30:15–16) Quietness would have made them strong, but they wouldn’t have it. Assyria was bearing down on Judah, threatening to crush them as it had crushed many before them. And how do God’s people respond? “Ah, stubborn children,” declares the Lord, “who carry out a plan, but not mine, and who make an alliance, but not of my Spirit, that they may add sin to sin; who set out to go down to Egypt, without asking for my direction.” (Isaiah 30:1–2) Even after watching him deliver them so many times before, they cast his plan aside and made their own. They sought help, but not from him. They went back to Egypt (of all places!) and asked those who had enslaved and oppressed them to protect them. And they didn’t even stop to ask what God thought. They did, and did, and did, at every turn refusing to stop, be quiet, and receive the strength and support of God. I would rush to help you, God says, but you were unwilling. You weren’t patient or humble enough to receive my help. “How often do we choose activity over quietness, distraction over meditation, ‘productivity’ over prayer?” Why would they refuse the sovereign help of God? Deep down, we know why. Because they felt safer doing what they could do on their own than they did waiting to see what God might do. How often do we do the same? How often do we choose activity over quietness, distraction over meditation, “productivity” over prayer? How often do we try to solve our problems without slowing down enough to first seek God? Consequences of Avoiding Quiet Self-reliance is, of course, not as productive as it promises to be — at least not in the ways we would want. The people’s refusal to be quiet and ask God for help not only cut them off from his strength, but also invited other painful consequences. First, the sin of self-reliance breeds more sin. Again, God says in verse 1, “‘Ah, stubborn children,’ declares the Lord, ‘who carry out a plan, but not mine, and who make an alliance, but not of my Spirit, that they may add sin to sin.” The more we refuse the strength of God, the more we invite temptations to sin. Quiet keeps us close to God and aware of him. A scarcity of quiet pushes him to the margins of our hearts, making room for Satan to plant and tend lies within us. Second, their refusal to be quiet before God made them vulnerable to irrational fear. Because they fought in their own strength, the Lord says, “A thousand shall flee at the threat of one; at the threat of five you shall flee” (Isaiah 30:17). A lone soldier will send a thousand into a panic. The whole nation will crumble and surrender to just five men. In other words, you will be controlled and oppressed by irrational fears. You’ll run away when no one’s chasing you. You’ll lose sleep when there’s nothing to worry about. And right when you’re about to experience a breakthrough, you’ll despair and give up. Fears swell and flourish as long as God remains small and peripheral. Quiet time with God, however, scatters those fears by enlarging and inflaming our thoughts of him. The weightiest warning, however, comes in verse 13: those who forsake God’s word, God’s help, God’s way invite sudden ruin. “This iniquity shall be to you like a breach in a high wall, bulging out and about to collapse, whose breaking comes suddenly, in an instant.” Confidence in self drove a crack in the strongholds around them — a crack that grew and spread until the walls collapsed on top of them. All because they refused to embrace quiet and trust God. “In quietness and trust would be our strength; in busyness and pride will be our downfall.” For Judah, ruin meant falling into the cruel hands of the Assyrians. The walls will fall differently for us, but fall they will, if we let busyness and noise keep us from dependence. In quietness and trust would be our strength; in busyness and pride will be our downfall. Mercy for the Self-Reliant In the rhythms of our lives, do we make time to be quiet before God? Do we expect God to do more for us while we sit and pray than we can do by pushing through without him? If verse 15 humbles us — “But you were unwilling . . .” — verse 18 should humble us all the more. As Judah hurries and worries and strategizes and plans and recruits help and works overtime, all the while avoiding God, how does God respond to them? What is he doing while they refuse to stop doing and be quiet? Therefore the Lord waits to be gracious to you, and therefore he exalts himself to show mercy to you. For the Lord is a God of justice; blessed are all those who wait for him. (Isaiah 30:18) While we refuse to wait for him, God waits to be gracious to us. He’s not watching to see if he’ll be forced to show us mercy; he wants to show us mercy. The God of heaven, the one before time, above time, and beyond time, waits for us to ask for help. He loves to hear the sound of quiet trust. Blessed — happy — are those who wait for him, who know their need for him, who ask him for help, who find their strength in his strength, who learn to be and stay quiet before him. Article by Marshall Segal