About the Book

"A Better Covenant" by Kenneth E. Hagin explores the New Covenant established by Jesus Christ and how believers can appropriate its benefits in their lives. The book discusses how the New Covenant is superior to the Old Covenant and provides insight into how Christians can walk in the fullness of God's promises through faith. Hagin emphasizes the importance of understanding and applying the principles of the New Covenant in order to experience true freedom and victory in Christ.

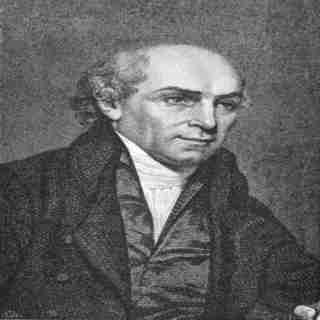

William Carey

"Expect great things; attempt great things."

At a meeting of Baptist leaders in the late 1700s, a newly ordained minister stood to argue for the value of overseas missions. He was abruptly interrupted by an older minister who said, "Young man, sit down! You are an enthusiast. When God pleases to convert the heathen, he'll do it without consulting you or me."

That such an attitude is inconceivable today is largely due to the subsequent efforts of that young man, William Carey.

Plodder Carey was raised in the obscure, rural village of Paulerpury, in the middle of England. He apprenticed in a local cobbler's shop, where the nominal Anglican was converted. He enthusiastically took up the faith, and though little educated, the young convert borrowed a Greek grammar and proceeded to teach himself New Testament Greek.

When his master died, he took up shoemaking in nearby Hackleton, where he met and married Dorothy Plackett, who soon gave birth to a daughter. But the apprentice cobbler's life was hard—the child died at age 2—and his pay was insufficient. Carey's family sunk into poverty and stayed there even after he took over the business.

"I can plod," he wrote later, "I can persevere to any definite pursuit." All the while, he continued his language studies, adding Hebrew and Latin, and became a preacher with the Particular Baptists. He also continued pursuing his lifelong interest in international affairs, especially the religious life of other cultures.

Carey was impressed with early Moravian missionaries and was increasingly dismayed at his fellow Protestants' lack of missions interest. In response, he penned An Enquiry into the Obligations of Christians to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens. He argued that Jesus' Great Commission applied to all Christians of all times, and he castigated fellow believers of his day for ignoring it: "Multitudes sit at ease and give themselves no concern about the far greater part of their fellow sinners, who to this day, are lost in ignorance and idolatry."

Carey didn't stop there: in 1792 he organized a missionary society, and at its inaugural meeting preached a sermon with the call, "Expect great things from God; attempt great things for God!" Within a year, Carey, John Thomas (a former surgeon), and Carey's family (which now included three boys, and another child on the way) were on a ship headed for India.

Stranger in a strange land

Thomas and Carey had grossly underestimated what it would cost to live in India, and Carey's early years there were miserable. When Thomas deserted the enterprise, Carey was forced to move his family repeatedly as he sought employment that could sustain them. Illness racked the family, and loneliness and regret set it: "I am in a strange land," he wrote, "no Christian friend, a large family, and nothing to supply their wants." But he also retained hope: "Well, I have God, and his word is sure."

He learned Bengali with the help of a pundit, and in a few weeks began translating the Bible into Bengali and preaching to small gatherings.

When Carey himself contracted malaria, and then his 5-year-old Peter died of dysentery, it became too much for his wife, Dorothy, whose mental health deteriorated rapidly. She suffered delusions, accusing Carey of adultery and threatening him with a knife. She eventually had to be confined to a room and physically restrained.

"This is indeed the valley of the shadow of death to me," Carey wrote, though characteristically added, "But I rejoice that I am here notwithstanding; and God is here."

Gift of tongues

In October 1799, things finally turned. He was invited to locate in a Danish settlement in Serampore, near Calcutta. He was now under the protection of the Danes, who permitted him to preach legally (in the British-controlled areas of India, all of Carey's missionary work had been illegal).

Carey was joined by William Ward, a printer, and Joshua and Hanna Marshman, teachers. Mission finances increased considerably as Ward began securing government printing contracts, the Marshmans opened schools for children, and Carey began teaching at Fort William College in Calcutta.

In December 1800, after seven years of missionary labor, Carey baptized his first convert, Krishna Pal, and two months later, he published his first Bengali New Testament. With this and subsequent editions, Carey and his colleagues laid the foundation for the study of modern Bengali, which up to this time had been an "unsettled dialect."

Carey continued to expect great things; over the next 28 years, he and his pundits translated the entire Bible into India's major languages: Bengali, Oriya, Marathi, Hindi, Assamese, and Sanskrit and parts of 209 other languages and dialects.

He also sought social reform in India, including the abolition of infanticide, widow burning (sati), and assisted suicide. He and the Marshmans founded Serampore College in 1818, a divinity school for Indians, which today offers theological and liberal arts education for some 2,500 students.

By the time Carey died, he had spent 41 years in India without a furlough. His mission could count only some 700 converts in a nation of millions, but he had laid an impressive foundation of Bible translations, education, and social reform.

His greatest legacy was in the worldwide missionary movement of the nineteenth century that he inspired. Missionaries like Adoniram Judson, Hudson Taylor, and David Livingstone, among thousands of others, were impressed not only by Carey's example, but by his words "Expect great things; attempt great things." The history of nineteenth-century Protestant missions is in many ways an extended commentary on the phrase.

"Expect great things; attempt great things."

At a meeting of Baptist leaders in the late 1700s, a newly ordained minister stood to argue for the value of overseas missions. He was abruptly interrupted by an older minister who said, "Young man, sit down! You are an enthusiast. When God pleases to convert the heathen, he'll do it without consulting you or me."

That such an attitude is inconceivable today is largely due to the subsequent efforts of that young man, William Carey.

Plodder Carey was raised in the obscure, rural village of Paulerpury, in the middle of England. He apprenticed in a local cobbler's shop, where the nominal Anglican was converted. He enthusiastically took up the faith, and though little educated, the young convert borrowed a Greek grammar and proceeded to teach himself New Testament Greek.

When his master died, he took up shoemaking in nearby Hackleton, where he met and married Dorothy Plackett, who soon gave birth to a daughter. But the apprentice cobbler's life was hard—the child died at age 2—and his pay was insufficient. Carey's family sunk into poverty and stayed there even after he took over the business.

"I can plod," he wrote later, "I can persevere to any definite pursuit." All the while, he continued his language studies, adding Hebrew and Latin, and became a preacher with the Particular Baptists. He also continued pursuing his lifelong interest in international affairs, especially the religious life of other cultures.

Carey was impressed with early Moravian missionaries and was increasingly dismayed at his fellow Protestants' lack of missions interest. In response, he penned An Enquiry into the Obligations of Christians to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens. He argued that Jesus' Great Commission applied to all Christians of all times, and he castigated fellow believers of his day for ignoring it: "Multitudes sit at ease and give themselves no concern about the far greater part of their fellow sinners, who to this day, are lost in ignorance and idolatry."

Carey didn't stop there: in 1792 he organized a missionary society, and at its inaugural meeting preached a sermon with the call, "Expect great things from God; attempt great things for God!" Within a year, Carey, John Thomas (a former surgeon), and Carey's family (which now included three boys, and another child on the way) were on a ship headed for India.

Stranger in a strange land

Thomas and Carey had grossly underestimated what it would cost to live in India, and Carey's early years there were miserable. When Thomas deserted the enterprise, Carey was forced to move his family repeatedly as he sought employment that could sustain them. Illness racked the family, and loneliness and regret set it: "I am in a strange land," he wrote, "no Christian friend, a large family, and nothing to supply their wants." But he also retained hope: "Well, I have God, and his word is sure."

He learned Bengali with the help of a pundit, and in a few weeks began translating the Bible into Bengali and preaching to small gatherings.

When Carey himself contracted malaria, and then his 5-year-old Peter died of dysentery, it became too much for his wife, Dorothy, whose mental health deteriorated rapidly. She suffered delusions, accusing Carey of adultery and threatening him with a knife. She eventually had to be confined to a room and physically restrained.

"This is indeed the valley of the shadow of death to me," Carey wrote, though characteristically added, "But I rejoice that I am here notwithstanding; and God is here."

Gift of tongues

In October 1799, things finally turned. He was invited to locate in a Danish settlement in Serampore, near Calcutta. He was now under the protection of the Danes, who permitted him to preach legally (in the British-controlled areas of India, all of Carey's missionary work had been illegal).

Carey was joined by William Ward, a printer, and Joshua and Hanna Marshman, teachers. Mission finances increased considerably as Ward began securing government printing contracts, the Marshmans opened schools for children, and Carey began teaching at Fort William College in Calcutta.

In December 1800, after seven years of missionary labor, Carey baptized his first convert, Krishna Pal, and two months later, he published his first Bengali New Testament. With this and subsequent editions, Carey and his colleagues laid the foundation for the study of modern Bengali, which up to this time had been an "unsettled dialect."

Carey continued to expect great things; over the next 28 years, he and his pundits translated the entire Bible into India's major languages: Bengali, Oriya, Marathi, Hindi, Assamese, and Sanskrit and parts of 209 other languages and dialects.

He also sought social reform in India, including the abolition of infanticide, widow burning (sati), and assisted suicide. He and the Marshmans founded Serampore College in 1818, a divinity school for Indians, which today offers theological and liberal arts education for some 2,500 students.

By the time Carey died, he had spent 41 years in India without a furlough. His mission could count only some 700 converts in a nation of millions, but he had laid an impressive foundation of Bible translations, education, and social reform.

His greatest legacy was in the worldwide missionary movement of the nineteenth century that he inspired. Missionaries like Adoniram Judson, Hudson Taylor, and David Livingstone, among thousands of others, were impressed not only by Carey's example, but by his words "Expect great things; attempt great things." The history of nineteenth-century Protestant missions is in many ways an extended commentary on the phrase.

when they hurt you with words

The spirit of the old adage “words will never harm me” is not the sentiment of the Scriptures. Words can hurt, even when directed from an unknown profile online. God made a world in which words are powerful. “Death and life are in the power of the tongue” (Proverbs 18:21). And as public discourse falls to new lows in the digital age, God has not left us without a guide for how to respond to the pain when we are persecuted with words. Leaf through the New Testament, and you’ll find verbal attacks on Jesus, his apostles, and his church on nearly every page. At times, these attacks escalate to physical persecution — the stoning of Stephen, the martyrdom of James, the imprisonments of Peter and Paul, the crucifixion of Christ — but what remains constant, and significant, is a torrent of verbal persecution against Jesus and his people. And verbal persecution is not less than persecution because it’s verbal. Have You Been Reviled? Slander and revile are two of the main words for verbal attack in the English New Testament, and both occur frequently. Early Christians were so accustomed to being spoken against that they developed a rich vocabulary (if you call it that) of being slandered, reviled, insulted, maligned, mocked, and spoken evil against (at least six different Greek verbs, along with several related nouns and adjectives). Of the English terms, revile may be the least common in normal usage today. One dictionary defines it as “to criticize in an abusive or angrily insulting manner.” To take our cues from specific biblical texts, revile can mean “to speak evil against” (Matthew 5:11; Mark 9:39; Acts 19:9; 23:4); it is the opposite of verbally honoring someone (Mark 7:10). Reviling is an attempt to injure with words (1 Peter 3:16). We see it at Jesus’s crucifixion, where “those who passed by derided him” with their words, and the chief priests, scribes, and elders “mocked him,” and “the robbers who were crucified with him also reviled him in the same way” (Matthew 27:39–44). But Jesus not only endured it; he prepared us for it as well. He and his apostles, and the early church, model for us how to receive and respond to slander and reviling. 1. Expect the world to say the worst. Amid this rich vocabulary of verbal attack, the New Testament sends no mixed signals as to whether Christians will be maligned. We will. Jews and Gentiles together bombarded Jesus and his disciples with verbal attacks. Physical persecution came and went, but reviling remained constant. When Paul arrived in Rome, the Jews reported to him, about Christianity, “With regard to this sect we know that everywhere it is spoken against” (Acts 28:22). For Christians, being reviled is not a matter of if but when : “when they speak against you” (1 Peter 2:12). Unbelievers “are surprised when you do not join them in the same flood of debauchery” — so what do they do? “They malign you” (1 Peter 4:4). After all, should we not expect the world, under the power of the devil (1 John 5:19; Ephesians 2:2), to lie about us? The Greek for devil ( diabolos ) actually means slanderer (1 Timothy 3:11; Titus 2:3). As Jesus said to his revilers in John 8:44, “You are of your father the devil, and your will is to do your father’s desires. . . . When he lies, he speaks out of his own character, for he is a liar and the father of lies.” 2. Consider the cause. We should not assume that all verbal opposition we receive is good. Being reviled for Jesus’s sake and for his gospel is one thing; being reviled for our own folly and sin is another (1 Peter 3:17; 4:15–16). As far as it depends on us, we want to “give the adversary no occasion for slander” (1 Timothy 5:14). Slander itself is no win for the church. We want to do what we can, within reason and without compromise, to keep God’s name and word and teaching from reviling (1 Timothy 6:1; Titus 2:5). “Do not let what you regard as good be spoken of as evil” (Romans 14:16). But when the world speaks evil against us because of Jesus, we embrace it. “If you are insulted for the name of Christ , you are blessed, because the Spirit of glory and of God rests upon you” (1 Peter 4:14). 3. Do not revile in return. Christ’s calling to his church is crystal clear: Do not respond in kind. Do not stoop to the level of your revilers. “Keep your conduct honorable” (1 Peter 2:12). “Speak evil of no one” (Titus 3:2), including those who have spoken evil of you. Do not become a verbal vigilante, but “entrust yourself to him who judges justly” (1 Peter 2:23). And as his redeemed, taste the joy of walking in his steps: “When he was reviled, he did not revile in return” (1 Peter 2:23). Paul took up the same mantle: “When reviled, we bless; when persecuted, we endure; when slandered, we entreat” (1 Corinthians 4:12–13). So also Peter charges us to respond “with gentleness and respect, having a good conscience, so that, when you are slandered, those who revile your good behavior in Christ may be put to shame” (1 Peter 3:15–16). When we do not “revile in return,” we put our revilers to shame. Christians do not respond in kind. We lose the battle, and undermine our commission, when we let revilers make us into revilers. And it’s not just a matter of strategy, but of spiritual life and death. “Revilers,” 1 Corinthians 6:10 warns, “will not inherit the kingdom of God,” and Christians are instructed “not to associate with anyone who bears the name of brother if he is . . . a reviler” (1 Corinthians 5:11). Christ expects, even demands, that our speech be different from the world’s, even when we respond to the world’s mean words. 4. Leap for joy. Leap for joy? That might seem way over the top. Can’t we just take our cues from the apostles in Acts 5:41? “They left the presence of the council, rejoicing that they were counted worthy to suffer dishonor for the name.” Amen, rejoice. Yes. Jesus’s own words in the Sermon on the Mount guide us: “Blessed are you when others revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely on my account. Rejoice and be glad , for your reward is great in heaven, for so they persecuted the prophets who were before you.” (Matthew 5:11–12). But Luke 6:22–23 doesn’t leave it at simply rejoicing: “Blessed are you when people hate you and when they exclude you and revile you and spurn your name as evil, on account of the Son of Man! Rejoice in that day, and leap for joy , for behold, your reward is great in heaven; for so their fathers did to the prophets.” Whether you’re just rejoicing in God deep down, or finding the emotional wherewithal, in the Spirit, to “leap for joy,” the point is clear: When others dishonor you, and exclude you, and utter all manner of evil against you, and even spurn your name as evil — and that on Jesus’s account , not on the account of your own folly — this is not new, and you are not alone (“so their fathers did to the prophets”). You have a great cause for joy. Their reviling you for his sake means you are with him! And you will know him more as you share in the verbal persecution he endured (Philippians 3:10). 5. On the contrary, bless. There is one more shocking possibility for Christians, even more astounding than leaping for joy: “Do not repay evil for evil or reviling for reviling, but on the contrary, bless , for to this you were called, that you may obtain a blessing” (1 Peter 3:9). This indeed is the spirit of Christ, and gives the most striking testimony of the Spirit of Christ at work in us. The grace and power of God not only enable us to expect and evaluate reviling, and not respond in kind but even rejoice, but also repay reviling with blessing . This is Christlikeness. This is Christian maturity (Matthew 5:48). This reflects the magnanimous heart of our Father in heaven (Matthew 5:45). This is the enemy-love to which Jesus not only calls us but works in us by his Spirit. “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you” (Matthew 5:44). In Christ, we have found ourselves blessed when we deserved to be cursed. We have come to know a Father who does not revile those who humbly seek him (James 1:5). When reviled, we now have the opportunity to bless undeserving revilers, just as we have been blessed from above — and will be further blessed for doing so (“that you may obtain a blessing,” 1 Peter 3:9). The swelling ocean of reviling in our day is not just an obstacle to be endured. It is an opportunity for gospel advance — and for deeper joy.

.epub-160.webp)