Others like the books of acts Features >>

About the Book

"The Books of Acts" by Rick Joyner provides a deep dive into the biblical Book of Acts, highlighting the key lessons and principles for modern-day Christians to apply in their daily lives. Joyner's engaging writing style and insightful commentary make this book a valuable resource for those seeking to deepen their understanding of the early church and their own faith journey.

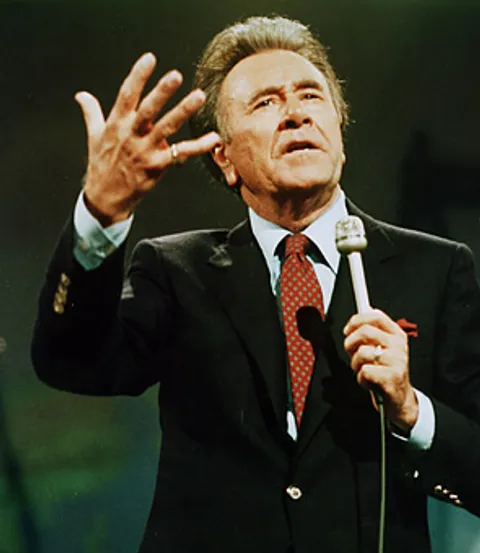

Oral Roberts

Granville Oral Roberts was born January 24, 1918 in Pontotoc County, near Ada, in Oklahoma. His parents were deeply religious. His father was a farmer who also preached the gospel and established Pentecostal Holiness churches. His mother regularly prayed for the sick and led people to Christ. While she was still pregnant, Robert's mother committed Oral to God's service. Even though Oral had a very strong stutter his mother would tell him that one day God would heal his tongue and he would speak to multitudes.

The Roberts family was desperately poor. When Roberts was 16 he moved away from home, hoping for a better life. He rejected God and his upbringing. He started living a wild life and his health collapsed. Roberts had contracted tuberculosis. He returned home and eventually dropped to 120 pounds. He was a walking skeleton. God spoke to his older sister, Jewel, and told her that He was going to heal Oral. During this same time Oral turned his heart back to God and gave his life to Christ. A traveling healing evangelist named George Moncey came to Ada and held meetings in a tent. Oral's elder brother was touched when he saw friends of his healed in the meeting. He decided that he should get Oral and bring him to be healed. On the way to the meeting God spoke to Oral and said "Son, I'm going to heal you and you are to take my healing power to your generation. You are to build me a University and build it on My authority and the Holy Spirit." Once at the meeting Oral waited until the very end. He was too sick to get up and receive prayer, and so had to wait for Moncey to come to him. At 11:00 at night his parents lifted him so he could stand. When Moncey prayed for him the power of God hit him and he was instantly healed. Not only that but every bit of his stutter was gone!

After Roberts was healed he began to travel the evangelistic circuit. He met and married Evelyn Lutman, a school teacher from the same Holiness Pentecostal background as Roberts. They had their first child Rebecca and then the entire family began traveling as ministers. In 1942 they left the evangelistic field for a while and Roberts became a pastor. He also returned to college to further his education. While a pastor he prayed for a church member whose foot was crushed. The foot was instantly healed. God continued to speak to Roberts about his call to the multitudes. God called him to an unusual fast. Roberts was to read the four gospels and the book of Acts three times consecutively, while on his knees, for thirty days. God began to reveal Jesus as the healer in a new way. God also began to give Roberts dreams where he would see people's needs as God saw them. God called him to hold a healing meeting in his town. A woman was dramatically healed, several people were saved and Roberts' ministry changed overnight.

Roberts resigned his church in 1947 and began an itinerant ministry. Notable healings began to occur. One man tried to shoot Roberts. God used the story to bring him media attention, which expanded his ministry very quickly. Roberts felt called to purchase a tent and take his evangelistic ministry to larger cities. His first tent held 3,000 but he quickly exchanged it for a tent that held 12,000. In July 1948 The Oral Roberts Evangelistic Association was established. Oral began traveling continuously throughout the United States. Like many of his Pentecostal brethren Roberts held inter-racial meetings. This brought him a lot of negative attention from groups who didn't like his stand. He even received death threats for not holding segregated meetings. In 1956 Roberts was invited to Australia. He held meetings in Sydney and Melbourne. In Melbourne there were outright physical attacks and destructive gangs. He was literally driven out of the city for praying for the sick. Often when people discuss the healing revival of the 1950s Oral Roberts and William Branham are listed as the most widely recognized leaders of the movement. Others came along side and many emulated them, but they were the most widely recognized personalities.

Roberts was a man who understood and used the media for his benefit. Roberts began publishing a magazine almost immediately upon starting his ministry. He grasped the power of radio and television. In 1954 Roberts began filming his crusades. He began playing his sermons on radio and then airing the crusade tapes during evening television prime time. Unfortunately there is some evidence that healing meetings were scripted ahead of time, and not all healings were genuine. People began writing to the Ministry headquarters by the thousands. They were accepting Christ as their savior after seeing a person healed on TV. By 1957 the ministry was receiving 1,000 letters a day and he was getting thousands of phone calls. He established a round the clock prayer team to answer calls and pray for people who contacted the ministry. In 1957 Roberts claimed 1,000,000 salvations. Between 1947 and 1968 Roberts conducted over 300 major Crusades. Money was flowing into the organization at an unprecedented rate.

In the late 1950s the healing movement was waning and ministries were under attack for their lack of financial accountability. Roberts began to move on the vision God gave him to build a University. It was chartered in 1963 and became open to students in 1965. Roberts was having a significant national impact in the late 1950s and early 1960s. For several years his named appeared in the Top 100 list of the nation's most respected people. Although Roberts continued to hold healing meetings his focus shifted to the University and the television programs.

The 1970s and 80s brought many crises to the Roberts family. Their daughter Rebecca and son-in-law Marshall were killed in a plane crash. Their son Ronnie struggled with depression after serving in Vietnam and also declaring himself gay. He grew despondent after losing his job and committed suicide. Richard Roberts got a divorce. After Richard remarried he and his wife lost a new born son within two days. Roberts began teaching a doctrine of "seed faith" where he claimed that if you gave to his ministry then God would pay you back in multiplied ways. The television ministry received heavy criticism for the constant requests for money. The Roberts were living an extravagance lifestyle while many of their supporters were not wealthy. Financial questions were raised in how Roberts used University endowment funds to purchase personal homes and cars.

In 1977 Roberts had a vision to build a hospital where people not only received care but received healing prayer. It was to be called City of Faith. Roberts put his heart and soul into the project, believing that God would build it as He had the University. The hospital struggled along and Roberts called his followers to give to the project, believing he had a vision from God to raise the money. Roberts even claimed twice that if money didn't come in that Jesus would "take him home." The hospital was built, but never succeeded financially, and finally closed in 1989. Financial giving was plummeting for both the Oral Roberts Evangelistic Association and Oral Roberts University.

Roberts retired in 1993, at the age of 75. Roberts, with his wife Evelyn, moved to California to live near the coast. Evelyn died in May 2005. Although Roberts influence waned after the problems of the 1970s and 1980s, he was still recognized for his pioneering work on the "sawdust trail", television evangelism, and building a Christian University. He often appeared on religious broadcasting networks as a recognized leader in the healing movement of the last half century. He died December 15, 2009 at the age of 91.

Oral Roberts' legacy is a mixed one. Roberts brought the truth of God's healing to the public in a way that few others accomplished in his lifetime. His financial and personal issues and increasingly extravagant claims eventually brought his ministry into disrepute. The University he established continued to have financial crises under the leadership of his son Richard Roberts. It was only after Richard stepped down in 2009 and new leadership took over the University that it stabilized financially. The University is no longer connected to the Oral Roberts Evangelistic Association.

Granville Oral Roberts was born January 24, 1918 in Pontotoc County, near Ada, in Oklahoma. His parents were deeply religious. His father was a farmer who also preached the gospel and established Pentecostal Holiness churches. His mother regularly prayed for the sick and led people to Christ. While she was still pregnant, Robert's mother committed Oral to God's service. Even though Oral had a very strong stutter his mother would tell him that one day God would heal his tongue and he would speak to multitudes.

The Roberts family was desperately poor. When Roberts was 16 he moved away from home, hoping for a better life. He rejected God and his upbringing. He started living a wild life and his health collapsed. Roberts had contracted tuberculosis. He returned home and eventually dropped to 120 pounds. He was a walking skeleton. God spoke to his older sister, Jewel, and told her that He was going to heal Oral. During this same time Oral turned his heart back to God and gave his life to Christ. A traveling healing evangelist named George Moncey came to Ada and held meetings in a tent. Oral's elder brother was touched when he saw friends of his healed in the meeting. He decided that he should get Oral and bring him to be healed. On the way to the meeting God spoke to Oral and said "Son, I'm going to heal you and you are to take my healing power to your generation. You are to build me a University and build it on My authority and the Holy Spirit." Once at the meeting Oral waited until the very end. He was too sick to get up and receive prayer, and so had to wait for Moncey to come to him. At 11:00 at night his parents lifted him so he could stand. When Moncey prayed for him the power of God hit him and he was instantly healed. Not only that but every bit of his stutter was gone!

After Roberts was healed he began to travel the evangelistic circuit. He met and married Evelyn Lutman, a school teacher from the same Holiness Pentecostal background as Roberts. They had their first child Rebecca and then the entire family began traveling as ministers. In 1942 they left the evangelistic field for a while and Roberts became a pastor. He also returned to college to further his education. While a pastor he prayed for a church member whose foot was crushed. The foot was instantly healed. God continued to speak to Roberts about his call to the multitudes. God called him to an unusual fast. Roberts was to read the four gospels and the book of Acts three times consecutively, while on his knees, for thirty days. God began to reveal Jesus as the healer in a new way. God also began to give Roberts dreams where he would see people's needs as God saw them. God called him to hold a healing meeting in his town. A woman was dramatically healed, several people were saved and Roberts' ministry changed overnight.

Roberts resigned his church in 1947 and began an itinerant ministry. Notable healings began to occur. One man tried to shoot Roberts. God used the story to bring him media attention, which expanded his ministry very quickly. Roberts felt called to purchase a tent and take his evangelistic ministry to larger cities. His first tent held 3,000 but he quickly exchanged it for a tent that held 12,000. In July 1948 The Oral Roberts Evangelistic Association was established. Oral began traveling continuously throughout the United States. Like many of his Pentecostal brethren Roberts held inter-racial meetings. This brought him a lot of negative attention from groups who didn't like his stand. He even received death threats for not holding segregated meetings. In 1956 Roberts was invited to Australia. He held meetings in Sydney and Melbourne. In Melbourne there were outright physical attacks and destructive gangs. He was literally driven out of the city for praying for the sick. Often when people discuss the healing revival of the 1950s Oral Roberts and William Branham are listed as the most widely recognized leaders of the movement. Others came along side and many emulated them, but they were the most widely recognized personalities.

Roberts was a man who understood and used the media for his benefit. Roberts began publishing a magazine almost immediately upon starting his ministry. He grasped the power of radio and television. In 1954 Roberts began filming his crusades. He began playing his sermons on radio and then airing the crusade tapes during evening television prime time. Unfortunately there is some evidence that healing meetings were scripted ahead of time, and not all healings were genuine. People began writing to the Ministry headquarters by the thousands. They were accepting Christ as their savior after seeing a person healed on TV. By 1957 the ministry was receiving 1,000 letters a day and he was getting thousands of phone calls. He established a round the clock prayer team to answer calls and pray for people who contacted the ministry. In 1957 Roberts claimed 1,000,000 salvations. Between 1947 and 1968 Roberts conducted over 300 major Crusades. Money was flowing into the organization at an unprecedented rate.

In the late 1950s the healing movement was waning and ministries were under attack for their lack of financial accountability. Roberts began to move on the vision God gave him to build a University. It was chartered in 1963 and became open to students in 1965. Roberts was having a significant national impact in the late 1950s and early 1960s. For several years his named appeared in the Top 100 list of the nation's most respected people. Although Roberts continued to hold healing meetings his focus shifted to the University and the television programs.

The 1970s and 80s brought many crises to the Roberts family. Their daughter Rebecca and son-in-law Marshall were killed in a plane crash. Their son Ronnie struggled with depression after serving in Vietnam and also declaring himself gay. He grew despondent after losing his job and committed suicide. Richard Roberts got a divorce. After Richard remarried he and his wife lost a new born son within two days. Roberts began teaching a doctrine of "seed faith" where he claimed that if you gave to his ministry then God would pay you back in multiplied ways. The television ministry received heavy criticism for the constant requests for money. The Roberts were living an extravagance lifestyle while many of their supporters were not wealthy. Financial questions were raised in how Roberts used University endowment funds to purchase personal homes and cars.

In 1977 Roberts had a vision to build a hospital where people not only received care but received healing prayer. It was to be called City of Faith. Roberts put his heart and soul into the project, believing that God would build it as He had the University. The hospital struggled along and Roberts called his followers to give to the project, believing he had a vision from God to raise the money. Roberts even claimed twice that if money didn't come in that Jesus would "take him home." The hospital was built, but never succeeded financially, and finally closed in 1989. Financial giving was plummeting for both the Oral Roberts Evangelistic Association and Oral Roberts University.

Roberts retired in 1993, at the age of 75. Roberts, with his wife Evelyn, moved to California to live near the coast. Evelyn died in May 2005. Although Roberts influence waned after the problems of the 1970s and 1980s, he was still recognized for his pioneering work on the "sawdust trail", television evangelism, and building a Christian University. He often appeared on religious broadcasting networks as a recognized leader in the healing movement of the last half century. He died December 15, 2009 at the age of 91.

Oral Roberts' legacy is a mixed one. Roberts brought the truth of God's healing to the public in a way that few others accomplished in his lifetime. His financial and personal issues and increasingly extravagant claims eventually brought his ministry into disrepute. The University he established continued to have financial crises under the leadership of his son Richard Roberts. It was only after Richard stepped down in 2009 and new leadership took over the University that it stabilized financially. The University is no longer connected to the Oral Roberts Evangelistic Association.

Friend, You Can Be Ready to Die

Years ago I read somewhere that, during the Victorian era, people talked often about death, and sex was the taboo subject. By now we have flipped it. We talk freely about sex, and death is the taboo subject. To me, what’s odd is this: even Christians shy away from talking about death. For crying out loud, we’re going to heaven! Why should we fear anything ? Our Lord died and rose again — for us. Yes, the blunt truth can seem intimidating. Here it is: We don’t need to go looking for it. Sooner or later, something bad will come find us and take us out. But why not accept that, and prepare for it, and rejoice our way through it? Thanks to the risen Jesus, death is no longer a crisis. It is now our release. So, Death, you sorry loser, we will outlive you by an eternity. We will even dance on your grave, when “death shall be no more” (Revelation 21:4). But for now, among the many ways to prepare for death — like buying life insurance, making a proper will, and so forth — here are two truths that can help you prevail when your moment comes. Both insights come from an obscure passage near the end of Deuteronomy. Your Final Obedience First, your death will be your final act of obedience in this world below. Near the end of his earthly life, Moses received a surprising command from God: Go up this mountain . . . and view the land of Canaan, which I am giving to the people of Israel for a possession. And die on the mountain which you go up . . . (Deuteronomy 32:49–50) Moses obeyed the command, by God’s grace. His death, therefore, was not his pathetic, crushing defeat; it was his final, climactic act of obedience. As you can see in the verse, it was even what we call a mountaintop experience. “Your death will be your final act of obedience in this world below.” Sadly, our deaths are usually painful and humiliating. But that’s obvious. Down beneath the surface appearances, the profound reality is this: your death too will be an act of obedience, for you too are God’s servant, like Moses. The Bible says about us all, “ Precious in the sight of the Lord is the death of his saints” (Psalm 116:15). He will not throw you away like a crumpled-up piece of trash. He will receive you as his treasured friend. Your death might be messy here on earth, but it will not be disgusting to God above. It will be, to him, “precious” — that is, valued and honored. It will be you obeying the One who said, “Follow me” (Matthew 4:19). You followed him with a first step, and you will follow him with a last step. And when you’re thinking about it, don’t worry about failing him at that final moment. He who commands you will also carry you. Given the grandeur of a Christian’s death, I have to admit that I have never seen a Christian funeral do justice to the magnitude of the moment. We try, but our services fall short. Only by faith, looking beyond our poor efforts at doing honor, can we truly savor the wonder of a Christian’s crowning glory. Even still, let’s make every Christian funeral as meaningful as it can be by believing and declaring the truth. A blood-bought sinner has just stepped on Satan’s neck and leapt up into eternal happiness, by God’s grace and for his glory. The day of your funeral, this uncomprehending world will stumble along in its oblivious way. But your believing family and friends will understand what’s really going on. And they will rejoice. This being so, why not look forward to dying? Paul was so eager for his day of release, he honestly couldn’t decide whether he’d rather keep serving Jesus here or die and go be with Jesus there: “What shall I choose? I do not know! I am torn between the two” (Philippians 1:22–23 NIV). When our work here is finally complete, why stay one moment longer? Of course, just as God decides our birthday (which we do know), so God also decides our deathday (which we do not know). Let’s bow to his schedule. But right now, by faith, let’s also start sitting on the edge of our seats in eager anticipation. And when he does give the command, “Die,” we then can say, “Yes, Lord! At long last!” And we will die. He will help us obey him even then — especially then. Your Happy Meeting Second, your death will be your happy meeting with the saints in that world above. Not only did God command Moses to die, but he also deepened and enriched Moses’s expectations of his death: Die on the mountain which you go up, and be gathered to your people, as Aaron your brother died in Mount Hor and was gathered to his people. (Deuteronomy 32:50) To be with our Lord in heaven above is the ultimate human experience. But he himself includes in that sacred privilege “the communion of saints,” to quote the Apostles’ Creed. When you die, like Moses, you will be gathered to your people — all the believers in Jesus who have gone before you into the presence of God. Heaven will not be solitary you with Jesus alone. It will be you with countless others, surrounding his throne of grace, all of you glorifying and enjoying him together with explosive enthusiasm (Revelation 7:9–10). Right now, in this world, we are “the church militant,” to use the traditional wording. But even now, we are one with “the church triumphant” above. And when we die, we finally enter into the full experience of the blood-bought communion of saints. Think about it. No church splits, no broken relationships, not even chilly aloofness. We all will be united before Christ in a celebration of his salvation too joyous for any petty smallness to sneak into our hearts. You will like everyone there, and everyone there will like you too. You will be included. You will be understood. You will be safe. No one will kick you out, no one will bully you, no one will slander you — not in the presence of the King. And you will never again, even once, even a little, disappoint anyone else or hurt their feelings or let them down. You will be magnificent, like everyone around you, for Jesus will put his glory upon us all. Facing Death with Calm Confidence Even now, by God’s grace, we have come to the heavenly Jerusalem, and to innumerable angels in festal gathering, and to the assembly of the firstborn who are enrolled in heaven, and to God, the judge of all, and to the spirits of the righteous made perfect, and to Jesus, the mediator of a new covenant. (Hebrews 12:22–24) “Why should we, citizens of the heavenly city, ever fear anything about earthly death?” They all are there, right at this very moment, in the invisible realm. It’s only an inch away. And the instant after your last breath in this dark world, you will awaken to that bright world above, where you will be welcomed in and rejoiced over. Saint Augustine might smile and nod with deep dignity. Martin Luther might give you a warm bear hug. Elisabeth Elliot might gently shake your hand. And maybe for the first time ever, you’ll discover how good it feels to really belong . Here’s my point. Why should we, citizens of the heavenly city, ever fear anything about earthly death? By faith in God’s promises in the gospel, let’s get ready now so that we face it then with calm confidence — and even with bold defiance.

-160.webp)