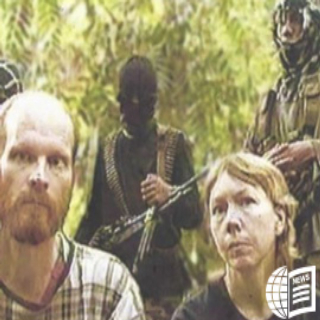

Martin and Gracia Burnham

Martin Burnham and Gracia were missionaries who served for 17 years in the Philippines. After their marriage, they underwent hard training in the jungle to prepare themselves to serve in jungle parts. Martin, being a pilot missionary, supported other missionaries who were working among the tribals in jungles. He delivered groceries and medicines to missionaries and tribals and transported sick people to medical facilities. He always had a big heart for tribals and missionaries. Gracia supported him well in the work.

On May 29, 2001, while relaxing at a resort after Martin’s one overseas mission, a Muslim militant group called the Abu Sayyaf Group attacked the resort and abducted the missionary couple and few others for ransom. The missionaries were kept captive for more than a year.

During that one year, the couple went through terrible experiences. They suffered starvation, sleeplessness and sickness, witnessed atrocities of militants and experienced gun battles between militants and the military. Amidst suffering, God was their only hope and strength.

At some point, Gracia was so depressed that although she believed that Christ died for her, she felt God doesn’t love her anymore. Martin said to her “either you believe it all or don’t believe it at all.” They encouraged one another to stand firm in the faith.

Martin Burnham and Gracia ministry in Philippines

Finally, on June 7, 2002, in a rescue operation by the Philippine military, wounded Gracia was rescued. But 42 years old Martin died in the gunfight during the rescue. Later, Gracia went back to America and joined her children.

Gracia did not let her painful experiences depress her and move her away from God. But she used those experiences to encourage others who are going through hardships. She founded the Martin and Gracia Burnham Foundation, which supports missionary aviation and tribal mission work around the world. It also focuses on ministries among Muslims. She forgave who abducted them, visited them in jail and shared Christ’s love. Some of them accepted Christ. Gracia believes that this may be God’s great purpose behind their suffering.

Martin Burnham and Gracia were missionaries who served for 17 years in the Philippines. After their marriage, they underwent hard training in the jungle to prepare themselves to serve in jungle parts. Martin, being a pilot missionary, supported other missionaries who were working among the tribals in jungles. He delivered groceries and medicines to missionaries and tribals and transported sick people to medical facilities. He always had a big heart for tribals and missionaries. Gracia supported him well in the work.

On May 29, 2001, while relaxing at a resort after Martin’s one overseas mission, a Muslim militant group called the Abu Sayyaf Group attacked the resort and abducted the missionary couple and few others for ransom. The missionaries were kept captive for more than a year.

During that one year, the couple went through terrible experiences. They suffered starvation, sleeplessness and sickness, witnessed atrocities of militants and experienced gun battles between militants and the military. Amidst suffering, God was their only hope and strength.

At some point, Gracia was so depressed that although she believed that Christ died for her, she felt God doesn’t love her anymore. Martin said to her “either you believe it all or don’t believe it at all.” They encouraged one another to stand firm in the faith.

Martin Burnham and Gracia ministry in Philippines

Finally, on June 7, 2002, in a rescue operation by the Philippine military, wounded Gracia was rescued. But 42 years old Martin died in the gunfight during the rescue. Later, Gracia went back to America and joined her children.

Gracia did not let her painful experiences depress her and move her away from God. But she used those experiences to encourage others who are going through hardships. She founded the Martin and Gracia Burnham Foundation, which supports missionary aviation and tribal mission work around the world. It also focuses on ministries among Muslims. She forgave who abducted them, visited them in jail and shared Christ’s love. Some of them accepted Christ. Gracia believes that this may be God’s great purpose behind their suffering.

slain in the shadow of the almighty

He who dwells in the shelter of the Most High will abide in the shadow of the Almighty . I will say to the Lord, “My refuge and my fortress, my God, in whom I trust.” (Psalm 91:1–2) On January 8, 1956, Jim Elliot, Nate Saint, Ed McCully, Peter Flemming, and Roger Youderian were speared to death on a sandbar called “Palm Beach” in the Curaray River of Ecuador. They were trying to reach the Huaorani Indians for the first time in history with the gospel of Jesus Christ. Elisabeth Elliot memorialized the story in her book Shadow of the Almighty . That title comes from Psalm 91:1: “He who dwells in the shelter of the Most High will abide in the shadow of the Almighty .” Not an Accident This is where Jim Elliot was slain — in the shadow of the Almighty. Elisabeth had not forgotten the heartbreaking facts when she chose that title two years after her husband’s death. When he was killed, they had been married three years and had a ten-month-old daughter. “God’s refuge for his people is not from suffering and death, but final and ultimate defeat.” The title was not a slip — not any more than the death of the five missionaries was a slip. But the world saw it differently. Around the world, the death of these young men was called a tragic nightmare. Elisabeth believed the world was missing something. She wrote, “The world did not recognize the truth of the second clause in Jim Elliot’s credo: ‘He is no fool who gives what he cannot keep to gain what he cannot lose .’” She called her book Shadow of the Almighty because she was utterly convinced that the refuge of the people of God is not a refuge from suffering and death, but a refuge from final and ultimate defeat. “Whoever would save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake will save it” (Luke 9:24) — because the Lord is God Almighty . God did not exercise his omnipotence to deliver Jesus from the cross. Nor will he exercise it to deliver you and me from tribulation. “If they persecuted me, they will also persecute you” (John 15:20). If we have the faith and single-mindedness and courage of those five missionaries, we might find ourselves saying with the apostle Paul, “For your sake we are being killed all the day long; we are regarded as sheep to be slaughtered.” No, in all these things we are more than conquerors through him who loved us. For I am sure that neither death nor life, nor angels nor rulers, nor things present nor things to come, nor powers, nor height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord. (Romans 8:36–39) Security in His Strength Has it ever hit home to you what it means to say, “My God, who loves me and gave himself for me, is almighty ”? It means that if you take your place “in the shadow of the Almighty,” you will be protected by omnipotence. There is infinite and unending security in the almightiness of God — no matter what happens in this life. “There is infinite, unending security in the almightiness of God — no matter what happens in this life.” The omnipotence of God means eternal, unshakable refuge in the everlasting glory of God, no matter what happens on this earth. And that confidence is the power of radical obedience to the call of God — even the call to die. Is there anything more freeing, more thrilling, or more strengthening than the truth that God Almighty is your refuge — all day, every day, in all the ordinary and extraordinary experiences of life? Nothing but what he ordains for your good befalls you. God Intervened Research into the circumstances surrounding the martyrdom of the five missionaries has revealed the hand of God in unexpected ways. In the September 1996 issue of Christianity Today , Steve Saint, son of Nate Saint, who was martyred along with Elliott, McCully, Flemming, and Youderian, wrote an article about new discoveries made about the tribal intrigue behind the slayings. He wrote one of the most amazing sentences on the sovereignty of the Almighty that I have ever read — especially coming from the son of a slain missionary: As [the killers] described their recollections, it occurred to me how incredibly unlikely it was that the Palm Beach killing took place at all; it is an anomaly that I cannot explain outside of divine intervention . (italics added) In other words, there is only one explanation for why these five young men died and left a legacy that has inspired thousands. God intervened. This is the kind of sovereignty we mean when we say, “Nothing but what he ordains for your good befalls you.” “In the darkest moments of our pain, God is hiding his weapons behind enemy lines.” Which also means that no one, absolutely no one, can frustrate the designs of God to fulfill his missionary plans for the nations. In the darkest moments of our pain, God is hiding his weapons behind enemy lines. Everything that happens in history will serve this purpose as expressed in Psalm 86:9, All the nations you have made shall come and worship before you, O Lord, and shall glorify your name. If we believed this, if we really let this truth of God’s omnipotence get hold of us — that we live perfectly secure in the shadow of the Almighty — what a difference it would make in our personal lives and in our families and churches. How humble and powerful we would become for the saving purposes of God.