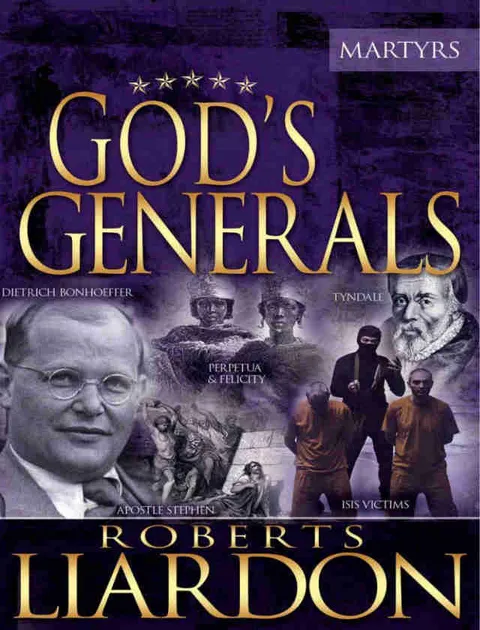

God's Generals: The Healing Evangelists Order Printed Copy

- Author: Roberts Liardon

- Size: 1.03MB | 271 pages

- |

Others like god's generals: the healing evangelists Features >>

God's Generals: Jack Coe

God's Generals - The Revivalists

God's Generals: Why They Succeeded And Why Some Failed

-160.webp)

God's Generals (Maria Woodworth)

-160.webp)

God's Generals (A. A. Allen)

God's Generals: The Martyrs

-160.webp)

God's Generals (William J. Seymour)

God's Generals - The Missionaries

God's Generals - The Martyrs

God's Generals: William Branham

About the Book

"God's Generals: The Healing Evangelists" by Roberts Liardon is a comprehensive account of the lives and ministries of some of the most influential healing evangelists in Christian history. This book provides insight into the lives, faith, and impact of individuals such as Oral Roberts, A.A. Allen, Kathryn Kuhlman, and others who played a significant role in spreading the message of healing and restoration through their powerful preaching and miraculous healings. Liardon's engaging narrative offers a powerful exploration of the work of these healing evangelists and their enduring influence on the faith and practice of Christianity.

Charles Wesley

blessed even in the worst - how to give thanks in every circumstance

A couple of years ago, social media revolted against the hashtag #blessed. It often seemed to be employed to brag about expensive vacations or impressive accomplishments under the guise of humility. But home décor stores do not seem to have gotten the message. They have shelves stocked with all kinds of signs and accessories so we can declare to the world — or at least anyone who comes into our houses — that we are indeed “blessed.” But what do we mean when we say that we are blessed? Is it an expression of gratitude for the things we have, the health we enjoy, or the people we love? Are these things really at the center of what it means to be blessed? The Source of Blessing From the first chapter to the last, the Bible’s story is one of blessing — blessing pronounced, blessing promised, blessing anticipated, and blessing experienced. We begin to get a sense of what it really means to be blessed in Numbers 6:22–27: The Lord spoke to Moses, saying, “Speak to Aaron and his sons, saying, Thus you shall bless the people of Israel: you shall say to them, The Lord bless you and keep you; the Lord make his face to shine upon you and be gracious to you; the Lord lift up his countenance upon you and give you peace. So shall they put my name upon the people of Israel, and I will bless them.” These words were not given for Israel’s priests to use to ask God for his blessing, leaving them to wonder whether or not God would give it. Rather, God took the initiative to assure his people of his settled intention to bless them. He seemed to want to make it clear that he intended to be personally involved in their lives as the source of all the goodness they would enjoy. So the first thing we learn from this blessing is that God is the source of every blessing in our lives. He blesses us by keeping us secure, extending his grace, and flooding our lives with his healing and wholeness. He is fully engaged, fully determined, and fully able to fill our lives with the security, grace, and peace we all long for. The Substance of Blessing But he is more than the source of blessing; God is also the substance of blessing. Experiencing God’s blessing is not merely getting good things from God. The essence of blessing is getting more of God. It is looking up to see affection and approval radiating from his face. To be blessed is to be confident that God has not and will never ignore or abandon us. “Anything and everything good that emerges from our lives will be a result of God’s sovereign presence in it.” Since more of God himself is the substance of blessing, whenever we ask him to bless us, we’re essentially inviting him to pervade all of the ordinary aspects of our lives. When we ask him to bless our plans, we’re inviting him into them, inviting him to even disrupt or change them, believing that his plans are always better than ours. In asking for his blessing we’re confessing that the outcome of our lives will not be the sum of our grand efforts or accomplishments. Instead, anything and everything good that emerges from our lives will be a result of his sovereign presence in it. Blessed Even at the Worst Times If we really believe that God is the substance of blessing, we won’t confess that we’re blessed only in the circumstances that seem good. Instead, when times are hard, and even when the worst things we can imagine are happening to us, we’ll be able to say that we are blessed. We’ll call ourselves blessed and mean it because we’re experiencing the presence of God with us and in us — in ways we were barely aware of when life seemed easy. Because we know the Lord is keeping us and being gracious to us, our sense of security and peace won’t be so tied to our circumstances. In our desperation for him during difficult times, we’ll find ourselves incredibly blessed by an increased sense of his companionship and comfort. The Reason God Can Bless Us So how is it that God can be so good to us? On what basis can God bless us so generously? You and I can anticipate being showered with God’s blessing only because Jesus experienced the full measure of God’s curse in our place. Christ was given what we deserve so that we might be given what Christ deserves. This is the too-good-to-be-trueness of the gospel. “We enjoy God’s blessing only because Jesus experienced the full measure of God’s curse in our place.” We can be sure that the Lord will keep and protect us because Christ was not protected. We can revel in having the Lord’s face turned toward us only because he turned his face away from his own Son as he hung on the cross. We can be sure that the Lord will lift up his countenance upon us only because when he looks at us, he sees us robed in the righteousness of Christ. He is able to grant us his peace only because his anger was exhausted on another. To be blessed is to be joined to Christ so securely that we have an ever-increasing sense that we are being kept by and for God. Because we are recipients of lavish grace, we can be honest with God and other people about our sin. Because the Lord is giving us peace, we can face the future confident that there is therefore now no condemnation for us because we are in Christ Jesus (Romans 8:1). We can shout it for the world to hear, post it for the social media world to read, and nail it to every wall in our home: we are truly, deeply, eternally blessed in Christ.